- Home

- Carol Bruneau

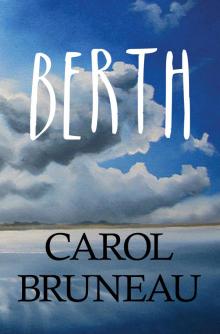

Berth

Berth Read online

Praise for Berth

Nominated for the 2006 ReLit Award

“A subtle work of offhand wisdom and insight, heartbreakingly true-to-life.”

–Lynn Coady

“Berth is excoriating in its illumination of women who are dependent, and how love (in its most romantic sense) can be utterly destructive.”

–The Globe and Mail

“Berth is a novel about taking chances with one’s heart and what happens when you cast off the present for a questionable future… The emotions in the novel are raw ones, the writing empathetic and skilled. A Nova Scotia novel with a difference, Berth is a winner.”

–The Sun Times (Owen Sound)

Also by Carol Bruneau

After the Angel Mill

Depth Rapture

Purple for Sky

Glass Voices

These Good Hands

A Bird on Every Tree

A Circle on the Surface

Copyright © 2005, 2018 Carol Bruneau

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Vagrant Press is an imprint of

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3660 Strawberry Hill Street, Halifax, NS, B3K 5A9

(902) 455-4286 nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

NB1348

Cover image: High Tide by Lynn Misner, 18 x 36, oil.

Design: Jenn Embree

This story is a work of fiction. Names, characters, incidents, and places, including organizations and institutions, either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Bruneau, Carol, 1956-, author

Berth : a novel / Carol Bruneau.

Reprint. Originally published: Toronto: Cormorant Books, 2005.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77108-616-5 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77108-632-5 (HTML)

I. Title.

PS8553.R854B47 2018C813’.54C2018-902864-5

C2018-902865-3

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Province of Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians.

To the lightship of friends

O abyss, O eternal Godhead, O sea profound, what more could you give me than yourself?

— Saint Catherine of Siena (1347-1380)

1

WINDS

You can have a heart as big as the sky, and hate flying. I have always hated it. The turbulence. The takeoff: that upwards thrust like an orgasm backwards. Like being blown awake, penetrating the clouds. That blind faith, a sweaty belief almost that you’ve sprouted wings. Feathers. And then the landing.

Go figure, then, that I’d married military. Air force, to be exact.

I hated flying so much, I’d just driven four thousand miles to avoid it. My boy and me, the station wagon loaded down like the Clampetts’ truck. “Pedal to the metal,” Sonny—Alex, his real name—sang out the whole way across Canada, from Vancouver Island to Nova Scotia. “What d’you think Dad’s doing right now?”

Charlie flew, our little family uprooted like a dandelion. A new base, a new edge of the country. Four thousand miles. Our lives still in boxes, barely time to shower. Blown in like weeds, Sonny and me. And guess what? Just in time for Family Day.

The tarmac felt like moving metal, my foot still bent from the accelerator.

Sit down, shut up, and hold on: to quote the famous bumper sticker. Advice I wanted to follow right now, gazing up at spacious blue. At least the sky here looked the same; that was one small comfort. Up, up, and away. Up where the air is clear. Up, up into the atmosphere. Let’s go fly a kite.

Holy good shit. As if you could trust the sky, something that sucked and vacuumed things up, all that blue. Water, spirits. Up into heaven, if you believed in that sort of thing, which I didn’t. And here I was with Sonny waiting in a line-up to fly, of all things. One of a flock of moms and kids getting a taste. A chance to go up in a helicopter, a taste of what made our husbands high: the work they did to feed us.

The chopper looked endangered, a prehistoric dragonfly buzzing on the concrete.

There was a lady flipping hot dogs, handing them out on serviettes. “New posting?” Her brows lifted.

I’d have chatted with her, if not for the roar of rotor blades. Operation Get Acquainted, said the badge on her apron. “Kind of late, isn’t it?” I nudged Charlie. He was clapping a helmet on Sonny’s—Alex’s—head. It slid down Sonny’s forehead like a basket that was too big.

The sun beat down, the runway like a beach with sand the colour of old chinos.

“I’m Joyce,” the lady said, swatting flies. “Joyce LeBlanc. I’m three doors up on Avenger.” The relish was green and sticky. “’Nother dog, sweetie?”

Charlie helped Sonny into a vest, one made of Kevlar that fit like a dress. His shorts drooped below it, his calves like white baseball bats. All nerves and bounce, he pushed to the head of the line.

“Keep your shirt on,” Charlie hollered. Then, to me: “Coming?”

The hot dog lady beamed. “Just hope for the best.” She, I noticed, was staying grounded. It wasn’t clear who she meant it for, me or the gal behind cradling a toddler. “Always hope for the best.”

Charlie laughed. Sweat wormed under my T-shirt. “Coming?” he yelled again.

Maybe it was PMS, maybe I’m a little bit crazy. But I’d have done anything to grab those tongs, serve wieners, and swat away flies. Anything to keep my feet on the runway.

Fears are just thoughts, I told myself. Just thoughts.

Charlie was giving me the eye, that look that says pee or get off the pot.

Just then the sky filled with shadows, birds cutting the glare.

“Willa!” Charlie’s voice was worse than a traffic jam, worse than a fleabag motel with no pool. “You coming, or not?” His face bloomed from the hatch—his face, and the navigator’s. The helo had swallowed Sonny.

Fear tasted like hot dog as I climbed the metal steps, let myself be eaten. And only because of Sonny.

Inside was a dingy sauna, but instead of bodies and sweat it stank of fuel. Instead of benches there was a seat like a canvas sling. Sonny grinned, a freckle-faced jack-o’-lantern. I grinned back, a death grimace.

The roar throbbed overhead, gnashing engines bearing down. We were in a cellar; any second we’d be bombed. A blast like the end of the world.

Charlie grabbed my wrist, pulled me down, strapped me in. The seat sagged like a camp cot. Sonny patted my knee. Families did this kind of thing all the time, his grin said. Look at Disney World. People pay money to get scared shitless. This is free.

My teeth ground together. All that weight, million-dollar engines pressing down. Metal fatigue, I thought. Charlie smirked with pride: no life like it. The air as heavy as an ocean flooding down. Clouds. Our skulls, tender as eggs fallen out of a nest.

As we rose, my stomach lagged. My face was frozen. Lockjaw. My back clammy with sweat.

Through the cockpit windows, between the pilot’s and co- pilot’s heads, a swath of concrete flashed. The hot dog lady, th

en the tops of trees: tiny dots growing tinier and tinier.

You’re in a car, I told myself. On a bus. Clenching Sonny’s hand.

Such a good kid, he didn’t pull it away. Charlie stared straight ahead, being kind.

My innards flew forward. The taste, again, of hot dog. We hovered, pressing up and up and up. Like Martians in our headsets, their weight holding in our brains. Then we thrust forward, like a kitten picked up and lugged by the scruff of its neck.

Out of body, out of mind. Drifting higher, higher. A kitten with its eyes not opened yet; no looking down.

Was this the art of detachment?

Sonny let go, rubbing the dents in his palm. The back of my shirt and green canvas were like the same cloth. Shaken loose, soot sifted down. Breathing, I tasted grease.

Then the mother cat yanked us short, jerked us sideways. Someone peeled back the cargo door. A blast of cold. The wrinkled blue sheen of water, the Atlantic a carpet rolling up into smooth, hazy azure. I glimpsed the green sprawl of an island, its shoreline a necklace. Pearls.

My stomach was helium, a black balloon. The rest of me an island like the one below, my heart a lagoon wrapped around Sonny.

Charlie’s jaw twitched. His lip curled in satisfaction. The feeling of leaving earth. Leaving it upside down maybe, boring through crust.

Pressing my knees apart, I strained against my harness, tried hanging my head. Shut my eyes as if, opened, all of me would leak through them. Something bumped the roof of my brain. Maybe this is what dying is like, the amoeba inside you that dreams pushing to get out.

Chugging in cold, I waited for it to be over.

When I looked again we were flying over glass and concrete towers. Capillary streets, cars like bright, beaded chemicals. We scooted along at a leisurely clip (faster, make it go faster!), our shadow below an escort.

“Having fun?” Charlie bellowed.

The peaks of a bridge loomed: steel mountain tops.

Charlie fitted a monkey tail to Sonny, a gunmetal-grey cable and boom. Manoeuvered him towards the gaping, rectangular light.

“No!” The engines chopped up my scream.

Sonny knelt there, that hazy blue melting by, an aura. A flash of green girders. He was sticking his head out, yelling something. Geronimoooooo! His body snapped tight against the edge of the hatch, his shorts and vest flapping back. He was screaming. Laughing.

Charlie hauled him back, slapping his knee. Sonny shouting.

My heart jackhammered. Tasting nitrates, petroleum, I anchored my eyes to wires running up the wall: arteries. Then studied circles on the floor, something to do with sonar: nerves. I searched for other circles, gauges, dials—the ones out of Charlie’s range.

Clumsy as a pup, Sonny patted my arm, his mouth opening, closing like a fish’s. “Don’t be a wuss, Mom. It’s not that scary. Not the Tilt-a-Whirl or Scrambler.”

Jerking forward, I kissed his cheek. Not the wisest thing to do, but some things you can’t help.

The warm-cool blush of his skin.

My worst fear suddenly vaporized. We’d made it. A gift, a reprieve like a magic bauble: a suncatcher, one of those glass things people hang in windows. We banked and started descending. Slowly, like a crippled geriatric going downstairs.

Touchdown. Relief was a hot-cold flash, with something else chafing inside. A hard little gem. Now I knew. This was it: where Charlie went when he disappeared, evaporated from our lives.

As my soles felt cement, somebody yelled: “Say SEX!” It was the hot dog woman still in her apron, aiming her Instamatic. Snap. The three of us caught there, in helmets and headsets. Like the Robinson family from Lost in Space, or Cold War-style aliens.

“Welcome aboard,” she squealed.

***

Two days later I was back on the tarmac—on terra firma, but no more grounded. The Dodge had died en route to the grocery store: the transmission? It was Sonny’s—Alex’s—first day at school, his new school, and any second he’d be out for lunch.

Where the heck was Charlie?

The sun baked down, hot for October. I’d left my shades in the car and had to shield my eyes, stepping from the hangar. The only shade was from the building, not a bush or tree in sight other than a blur of woods in the distance. A plastic banner flapped behind me, yellow in a riff of wind. Foreign Object Damage. Stay Alive. Be F.O.D. Smart.

The men formed a dragnet, a chain across the runway. Clones in their blue coveralls. Shadows pooled at their feet. I couldn’t make out a face, let alone anything so quirky as a moustache—if there’d been one. No weak links in this chain, not one straggler. Even their laughter sounded the same, snatches of it against the engines droning overhead.

Heat rippled as I stood there waving, hoping somebody would notice.

Every now and then one of them would rib another. Like guys on a ball field, or in a pub. Time out from the enemy, I thought: kids and wives. The Boys. The F.O.D. squad. Great.

A boxy woman in uniform eyed me as she slid past.

“Excuse me—?”

She kept going.

“Attention!” a voice barked and the chain tightened.

“Advance!” The chain inched forward, taut as wire, then knotted as someone stooped to pick something up. Nothing you could see with the naked eye.

Charlie’s voice boomed inside my head. One tiny stone, Willa. One ti-ny stone flies up, hits a compressor—you can kiss that engine goodbye. Not to mention the entire crew! Entire, he would stress. Charlie was the type who got ticked if you left crumbs on the counter.

I tried harder to make him out, waving frantically now. All I could think of was the Dodge sitting on the shoulder, the beefy guy in a truck who’d been good enough to stop. Shit.

Someone touched my arm. The uniformed woman. There were wings on her shirt.

“Personnel only. D’you have a pass?”

“My husband—” I threw up my hands.

“Wait inside. I’ll see what I can do.”

I followed her into the cool of the hangar. Five grey-green helicopters were parked inside, a couple missing tail sections. Another had lost its rotors; a hole gaped in its roof. Dragonflies, dead ones. Dismantled, they were even more awkward, quaint. At home Charlie called them relics; in a good mood he compared them to a sixties Corvette.

The servicewoman disappeared and I flagged down a brush cut who smelled of fuel.

“I’m looking for Charlie Jackson, my husband, and I’m—”

Cupping his mouth, he stepped outside, hollering loud enough to cut through anything. “Jackson? Buddy, your wife wants to talk to ya.”

Amazing, how it carried.

One of the links in the chain split off, shambling towards me. As Charlie’s features grew I forced a smile. He walked right past without saying hi, wiping something from his hands. Disappearing into an office, ducking out again, he gave me a pained look.

“The transmission, maybe?” I mouthed and heard him ask for the phonebook.

He took forever—calling a garage, I hoped. When he came out, the look on his face wasn’t good. “There’ll be someone down at one. Can you handle it?” Then he strode outside again—that is, if you can imagine someone that stocky, five-nine with a rolling gait, striding.

It was well past noon when I cleared the gates and made it down the hill to our house on Avenger Place. Sonny was on the front steps, kicking the concrete. He’d taken off his shirt; his stomach rolled over the top of his sweatpants. His backpack lay on the walk, a black banana poking from it.

“What took you so long? I’ve been waitin’ for hours.”

“How was school?”

“School stinks. My stomach hurts.”

I pushed past to let us in.

“I’m missing Batman. What’s for lunch?” Switching on the TV, he flopped into Charlie’s recliner. “Hey—wha’

d you do with the car?”

The volume rattled the window, rocked the furniture on the tiles.

“Turn it down, would you?”

I boiled hot dogs and flung them on a plate. Sonny was sprawled upside down, watching the news. An uprising in the Caribbean, people teeming through the streets like ants.

“Cool.” He chewed with his mouth open.

“Manners!”

“Why? No one’s watching.” He handed me his plate.

The next item involved missing people—runaways—the lack of “closure” for families. I was already grabbing my purse; it was a good twenty minutes back to the car.

“Don’t forget to lock up. Can you do that, d’you think?”

Outside, the sun had relented and it felt slightly more like fall. Our street, a long crescent, followed a rusty fence up a slope overlooking the water. It was as if God forgot to put trees on this side of the harbour or the wind had blown them to the opposite shore. Our neighbourhood, if you could call it that, clung to a hill, the whole thing hemmed in by barbed wire and WARNING signs.

The houses were the same, greyish pink, green, and turquoise shades, as if fog had seeped into the siding. We’d just moved in, so I should’ve been more forgiving. Except for the sameness, they almost looked like regular houses, but with no landscaping, no attempts at gardens or decks, things that had to be rooted and nailed down. There was grass though, short and yellow, with bursts of lushness near steps and foundations. And weeds, plenty of weeds, still thriving. If it was grim, the view redeemed it. Our first night, a windy one, you could feel the spray. On a day like this the harbour sparkled like crushed glass and looked almost warm.

I followed Avenger back to the gates, where the highway cut the base in two. Hard to figure why those gates existed; they were always open and rarely manned. Maybe to give the impression that we lived like civilians, which Charlie and I had yet to do. Moving was hard enough, Charlie said. Imagine living off base: it would be like having a cold that wasn’t bad enough to keep you home. If you were going to be sick, best to let it keep you in bed. In nearly ten years of married life, we’d known nothing else.

These Good Hands

These Good Hands A Circle on the Surface

A Circle on the Surface Glass Voices

Glass Voices Berth

Berth Brighten the Corner Where You Are

Brighten the Corner Where You Are A bird on every tree

A bird on every tree